A new life in a new world. That was the exciting proposition on offer to millions of Brits after the end of the Second World War. They took it up in their millions, but for many the reality fell some way short of the dream.

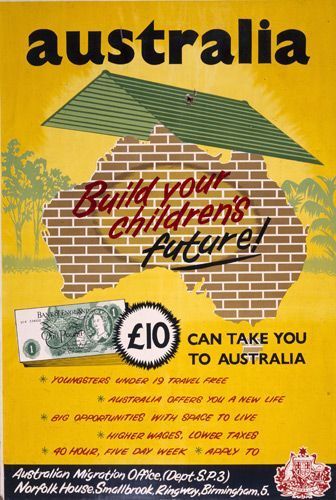

The deal was simple and attractive for just £10 they could travel to Australia and start a new life. It was all part of the Chilfley administrations ‘populate or die’ policy. They needed people and they needed them fast, so they looked to the old world to populate the new.

These ‘ten-pound poms’ would become central to Australia’s post war recovery and have left an indelible mark on the country.

Too good to be true

For Britons at the time, it looked like a great deal. Britain at the time was not a great place to be. Rationing was still imposed and, if you lacked an education, your prospects looked bleak. The idea of your own home, let alone your own piece of land, seemed like the stuff of fantasy.

Encouraged by adverts in glorious technicolor, depicting a tropical paradise they signed up in their millions. Around 400,000 made the trip in the first year alone. It was one of the biggest planned migrations of the 20th century and helped spark Australia’s economy into life. Before long, New Zealand had implemented a scheme of its own.

But there was a catch.

The policy was racist. Australia had a vision of its future and it was white. Black or Asian people were not invited.

Also, new workers had to commit to at least two years living in the new world. If they returned earlier, they would have to refund the price of the ticket. Likewise, there would be no low-cost route back home. If you got there and didn’t like it, getting home again would be tough.

That became a major issue once people realised the kind of life they were getting. While the trip for many was comfortable, the honeymoon came to an abrupt end once they hit land.

The new country they had come to was a work in development. Even today’s major hubs such as Perth were backwaters compared to what they’d known back home. As for the houses? Well, they, to put it mildly, were rough and ready.

Many had arrived without savings and had to put up with whatever accommodation the government provided. This often turned out to be Nissan huts, hostels or old army barracks. Conditions were tough and work was harder to find than most had expected.

Many quickly became disillusioned and simply waited out their two years until they could return to England. Australia’s media quickly dubbed these immigrants ‘whinging poms’, a name which still rings out in every Ashes cricket tour.

However, half of those who returned home changed their minds and returned to Australia to give it another crack. They became known as the boomerang poms.

A new life

It was not, then, the dream that many had expected, but for those who stuck it out there were opportunities to be had. If you found work and built-up savings, you could get out of the government hostels and start making a life for yourself.

£700 could buy you a house and your own plot of land, something which was unthinkable back home. While Britain was still dominated by class, this was a place where everyone was on the same footing. With hard work and a little luck, anyone could make a life for themselves.

As successful as it was, the scheme was limited. Britain could only supply so many white immigrants of the kind of stock Australia wanted. By the sixties, the government reluctantly realised it couldn’t secure enough migrants for its white Australia policy and opened it up to people of all races and backgrounds.

The scheme would continue until the early eighties. It had a major impact on the country. It fuelled rapid development and furnished Australia with two Prime Ministers. In 1966 Julia Gillard’s family took the trip from Barry in South Wales in the hope that the warm climate might cure her asthma. Six years previously, Tony Abbott had made the six-week trip with his family when he was two.

Other famous Australians to make the swich included Malcom and Angus Young from AC/DC as week as Robert and Barry Gibb who had grown up in Glasgow. Hugh Jackman’s and Kylie Minogue are both children of ten-pound poms.

While far from perfect, the scheme achieved its aim. Without it Australia today would have been a very different place.

Moving to Australia in 2021

Here at John Mason International Movers we give thousands of UK residents a ‘down under’ lifestyle every year. We’ve moved over 100,000 people to Australia in our history, so we know better than anyone what you need to consider and prepare for your big move. To help you plan, we have compiled the key information needed to immigrate abroad. If once you’ve digested it all you still have a few questions, give us a call – we’re on hand to help you in any way you need.

Your information about the £10 passage to Australia was very interesting. When people who decided to stay were they automatically given Australian Citizenship or did they have to apply for it?